Christmas is a time of rest, festive cheer, spending time with loved ones and (probably most importantly) food. This is seemingly not the case for academics. Firstly, Richard and I have been busy revising for our January finals, so whilst we’ve tried to give you a few juicy morsels over to tide you over the festive season, we’ve not really had chance to bring you the latest news. Coupled with this is that over this year’s festive period there’s been a lot of palaeontology going on. Holiday, what holiday?

So here is a What’s News(s) bumper edition, with 5 of the biggest news stories in palaeontology over the festive period. This week, we’ve got Saudi Arabian dinosaurs, naked dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs, body-size trends in evolution and some Hungarian palaeoneurobiology! Since we don’t want to spam you, we might start evolving our What’s New(s) sections so they are weekly, rather than as-and-when the news comes out (unless it’s really cool).

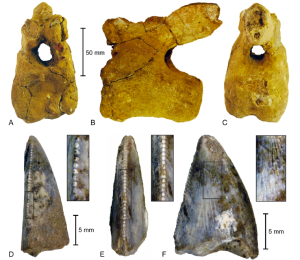

The first Saudi Arabian dinosaurs. Like has been previously stated, new dinosaur finds aren’t rare occurrences. They happen roughly every 1.5 weeks. Big deal right. Wrong (again). Benjamin Kear’s team have discovered a few caudal vertebrae and some teeth from Saudi Arabia, from the Maastrichtian (75 Ma, ish), and have confidently identified the vertebrae to be from a titanosaur, and the teeth to be from an abelisaurid. The confidence of these groupings is the first time that fossils the Arabian peninsula have been able to be classified as dinosaurian without contention. It also stretches the palaeogeographical ranges of titanosaurs and abelisaurids to the northern margin of Gondwana, whilst showing us (with just one find) that dinosaur ecology in this area may have been quite diverse in the mid-late Cretaceous. The papers also open access (over here on PloS One).

A-C: vertebra of a titanosaur from Saudi Arabia; D-F: tooth of a abelisaurid (again from Saudi Arabia). From Kear et al. (2013).

Naked dinosaurs a common sight during the Mesozoic. For a pretty ‘young’ blog, we’ve already mentioned naked dinosaurs (ooo err!) twice. That says a lot about Richard and I. Moving swiftly on… Since the discovery of the feathered Sinosauropteryx in 1996 (and a plethora of other feathered Chinese dinosaurs since) has caused a bit of frenzy. So much so, that even the Jurassic Park conceded, and created this monstrosity (they’ve now de-conceded, and have yet again ignored feathered dinosaurs). Since 1996, palaeontologists have endeavoured to find just how far back feathers go in the dinosaur lineage. Up until the early 2000s, we thought we had it covered, and that feathers were ancestral to theropods (with discoveries such as Dilong paradoxus, a feathered tyrannosaur sparking fierce debate over whether good old T. rex had a majestic feathered coat). Yet, as always, it only takes one discovery to turn everything upside down. Pscittacosaurus was that discovery. Pscittacosaurus is a ceratopsian (basal relative to the frilled dinosaur celebrity Triceratops), but with some proto-feathers. Crazy times.

Paul Barrett then set about to try and solve just where the feathered dinosaur bus stopped. He and his team looked at all of the dinosaur skin impressions found to date, looking for any sign of feathers (or similar structures) and then considered the data is a evolutionary context. He concluded that despite Pscittacosaurus, most ornithischians (ceratopsians, ornithopods, pachycephalosaurs and thyreophorans) and sauropods would have had scales. With the majority of dinosaurian clades having scales rather than feathers, Barrett tentatively concluded (at SVP 2013, in sunny Los Angeles) that scales were probably the ancestral condition in dinosaurs. But by now we know that all it takes is one feathered dinosaurs from the Triassic (or even the early Jurassic) to upheave this study.

The I(chthyosaur) of the Storm. Quick bit of local (for British palaeontologists anyhow) news for everyone. After heavy storms (no, seriously, before any Americans/Canadians/anywhere with ‘proper weather’ complain) a 1.5 m long partial ichthyosaur skeleton has been revealed at the base of a cliff in Dorset, and is being restored by the Jurassic Coast Heritage organisation. Three ichthyosaurs have been revealed in similar ways after storms in the past year along the Jurassic Coast. So remember kids, 80mp/h winds and floods aren’t all bad.

Growing fields: body-size trends throughout the fossil record. Whilst by no means is the study of body-size trends through evolutionary history a new field, but Mark Bell has just published a brilliant, relatively short and Open Access (whoop!) introduction to body-size trends in the fossil record. The article really does make you feel rather small (literally). It also goes through some long established rules on body-size evolution (e.g Cope’s rule), whilst also noting some nice examples of giganticism and dwarfism in the fossil record. Finally, he also states that new computer simulations/software maybe able to help us to further understand these trends in the future.

The very Hung-a-ry dinosaur brain. This gem of palaeontological news really does show how fieldwork and digital analysis can produce fantastic results. A new find of a partial skull of Hungarosaurus (from, you guessed it, Hungary) has enabled Hungarian palaeontologists to made a cast of the endocranial cavity, allowing them to analyse the braincase of this European anklyosaur. Initial results suggest that the cerebellum (area of the brain associated with motor control) is larger in volume than other ankylosaurs. This may well mean that Hungarosaurus was better able to run than other anklyosaurs (well known for not being the fastest of starters…).

References:

Kear BP, Rich TH, Vickers-Rich P, Ali MA, Al-Mufarreh YA, et al. (2013) First Dinosaurs from Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 8(12): e84041. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084041

Mayr, G., Peters, D. S., Plodowski, G. & Vogel, O. Naturwissenschaften 89, 361–365 (2002)

Zheng, X.-T., You, H.-L., Xu, X. & Dong, Z.-M. Nature 458, 333–336 (2009).

http://www.nature.com/news/feathers-were-the-exception-rather-than-the-rule-for-dinosaurs-1.14379

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-dorset-25548426

Patterns In Palaeontology: Trends of body-size evolution in the fossil record – a growing field

Ősi, Attila, Pereda Suberbiola, Xabier, and Földes, Tamás. 2014. Partial skull and endocranial cast of the ankylosaurian dinosaur Hungarosaurus from the Late Cretaceous of Hungary: implications for locomotion, Palaeontologia Electronica Vol. 17, Issue 1; 1A; 18p;

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2014/612-skull-of-hungarosaurus